Place-making strategies to achieve green justice in diverse neighbourhoods

It has been some time now that green infrastructure has caught my attention. My dissertation thesis on green strategies in diverse neighbourhoods in London was the beginning of a long research. This blog post is a short summary of my dissertation work.

A tree alongside the road, a garden, a park, green wedges. London is an example of a metropolitan city where the green coverage is deficit and the policy framework identifies it as a priority. The mayor’s vision is clear and emphasis is given on delivering the expected green coverage which will support economic growth and quality of life for the citizens. Is it that simple though? Is meeting the expected green coverage enough to achieve both economic growth and quality of life?

I believe the answer is not that straightforward. Green space cannot guarantee only positive outcomes. Central Park cannot prevent the high crime rate in some surrounding neighbourhoods around it nor the green spaces in diverse neighbourhoods in London can prevent social inequalities. Through my dissertation I tried to find the answer in that question using London and more specifically, a diverse neighbourhood in Tower Hamlets, as a case study.

FROM THEORY

Improving/regenerating places within the city to better the welfare of the citizens is not an easy process. As Harvey argues, not all the elements in the city system can be measured, which can eventually affect a city’s economy positively or negatively. These elements are called imperfections and green spaces belong to this category because they are public goods. Being a public good signifies that an element is non-excludable, non-rival and therefore it cannot be traded in the market nor calculated; this creates imperfections. In addition to this, based on Marx’s theory of value, those elements also tend to suffer exploitation since they are raw materials that have no-value in the monetary system. For that reason, any regeneration on green spaces should be done with careful consideration of the surroundings and the people living around instead of being treated as an accessory.

There are two prevailing green strategies that have been applied throughout the time to improve the people’s quality of life and achieve social inclusion in green spaces. These strategies are linked to two types of interaction between nature and the city that date back to when nature was only available to the people through the countryside. The first type of interaction is based on the notion that nature is the antidote to the city and that the aim should be to bring the countryside into the city. Gandy gives the term of seeming nature, the role of which is to bring the romanticism from the Enlightenment era to restore human spirit; nature is seen as a sacred element within the city but separated from it. The other type of interaction derives from the Malthusian era where it is supported that this romantic view of nature is not adequate. City’s complexity requires a throwntogether approach, as Amin believes, than a separation, since nothing is experienced by itself but always in relation to its surroundings. This approach is supported by Marx as well who argues that nature becomes a product itself when entering the city and its use should not be considered unlimited.

All-inclusive green strategy. This strategy treats each green space separately aiming to create equal products for the people living around them. This strategy derives from the first type of interaction with nature affected by the enlightenment era. For example, Olmsted designed Central Park following this strategy; implementing countryside into the city and welcoming everyone to visit it no matter the social-class. Today, this approach can be mostly seen in cases where planners, designers create ‘places for all’, places where everything can happen. The facilities/uses in the green spaces are over-determined in an attempt to create a well-balanced system where everyone coexists peacefully. However, as Sennett argues, expecting that someone will mix happily and share the space with someone else because of a sense of community is naïve. This approach of mixing everything in a place, is a characteristic of low quality. When the second type of interaction emerged, it became apparent that fairness in the system cannot be achieved only through equal distribution of goods. Social inequalities cannot be resolved only because everyone has the same proximity to a green space. A closer look is required to understand the complexity. This is when the park-system approach was developed.

Park-system green strategy. This strategy shifts the interest to the idea of a system that promotes openness and flexibility to any changes in the city fabric. The green spaces in a neighbourhood are not treated separately anymore, but in relation to the rest of the elements. The focus now is on the smaller scale. This approach has many supporters like Whyte proposing in particular that Central park is not the future anymore and that a city needs the equivalent of small spaces, or Cabe Space arguing that the emphasis should be made on quality rather than quantity and conviviality rather than exclusiveness. Abercrombie shared the same vision for a park-system concept for Great London’s Plan in 1943. He believed that the city should be equipped with a closely-linked park system where people could easily get from their doorstep to the garden, from the garden to the park, from the park to the parkway, from the parkway to green wedge and from green wedge to Green Belt. His concerns were the quality of the countryside and the maintenance or creation of open space. This could only happen by creating a nice flow starting from the city, so people could get use of the idea of nature before even reaching it. Thus, this approach in comparison to the all-inclusive vision, supports the notion that anything instead of everything can happen. As Imrie and Hall argue, the aim is not to treat everyone the same, but to develop policies and design principles that can accommodate a wider range of people.

TO PRACTICE

The Ocean Estate Neighbourhood was chosen as a case study to test the above theory. This area is located in Tower Hamlets borough, the 4rth diverse borough in the UK which is also known for taking initiatives on green strategies. In particular, Tower Hamlets is often used as an exemplar for design guidelines related to green spaces. The green coverage in the area is deficit and there is a variety of types and scales of green spaces. The site and desktop analysis and interviews focused on three aspects/objectives; the existing green policy framework of the area, the types of activities offered in the green spaces and park users’ preferences, backgrounds. The aim of the research was to examine which of the above green strategies has been applied in the neighbourhood and whether or not it has achieved social inclusion in the green spaces.

A map of the area is provided below showing the Ocean Estate Neighbourhood and the green spaces on which the reaseach and analysis was conducted.

POLICY FRAMEWORK

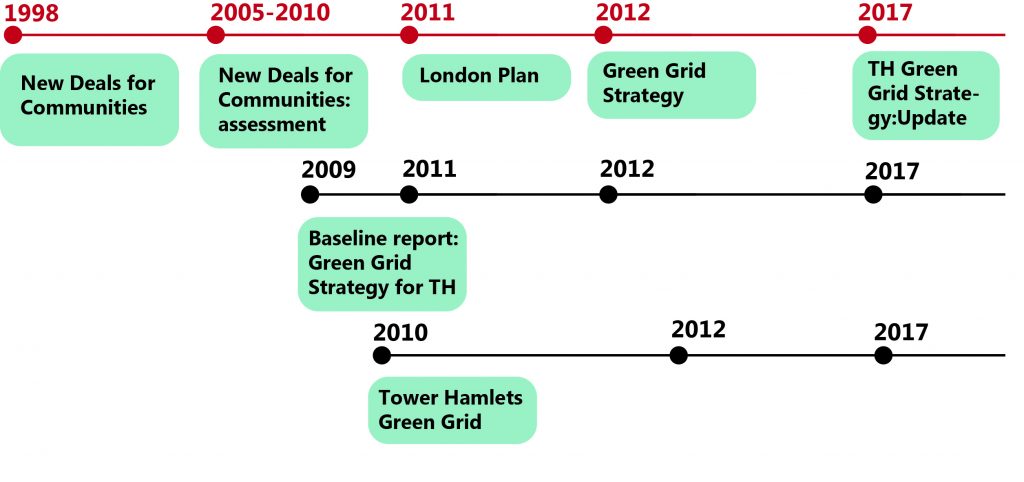

The policy framework gave an insight of the design principles used to regenerate the green spaces in the neighbourhood and also revealed the different ‘trends’ throughout the time. In particular, the regeneration scheme and green strategies plan are the ones presented below:

- New Deals for Communities program (1998-2010)

- Green Grid Strategy in Tower Hamlets (2009-2017)

The detailed timeline of the policy framework related to green spaces in Tower Hamlets and in London in general is presented below:

These two planning programs/strategies, athough applied in different periods of time, seem to align with the two types of interaction with nature as mentioned in the theory above. More specifically, the New Deals for Communities program (NDC) aimed to regenerate identified communities in decline in London and Ocean Estate was one of these communities. Green spaces were one of the priorities for the program and an important part of the total funding was given for their management. The people would participate in the process by collaborating with the local authorities. In other words, engaging people and giving them the opportunity to share their views, was seen as the solution to achieve social inclusion. However, their input was limited to the managerial context and the focus of the design interventions was only place-related to achieve faster outcomes. At the time, these measures were considered adequate to eliminate social inequalities between people and bridge the gaps in the communities. This strategy can be related to the first type of interaction with nature and the concept of the all-inclusive vision where nature, by being considered a sacred element, is not connected with the city and thus, it is studied/designed separated from it. The outcome of that process is green spaces of high-quality that are designed and managed by local authorities and the residents as well. However, little attention was paid to the demographics.

For that reason, the approach was later found insufficient and the focus started to change by paying more attention to the people themselves and to an effort to implement the local needs into design. This shift of interest overlaps with the Green Grid Strategy which introduced a new way of approaching green spaces and achieving inclusion in communities, whilst at the same time the London Plan was already welcoming this new way of thinking towards green spaces. The green strategy that came after the NDC program focused on both people and place-related interventions which were tailored to the demographic profile of the particular area. The emphasis was on linking the small-scale green spaces of the areas rather than treating them separately. This strategy can be related to the second type of interaction with nature and the concept of the park-system approach where nature is considered as an element which is entirely interconnected with the rest of the city, rather than a separated element as the all-inclusive vision supported.

It appears that both green strategies applied in Ocean Estate derived from the types of interaction with nature mentioned in the theory. This area is a proof that both green strategies were implemented and this makes it the perfect case study. Based on the interviews with people living in the area long enough to witness the implementation of both strategies, even unconsciously, there was a high percentage of them supporting that there has been some improvement in the green spaces. In particular, when they were asked to specify the kinds of improvement, they mentioned the design of the parks and the feeling of inclusion declaring that there is a variety of backgrounds using these spaces.

PARK USES

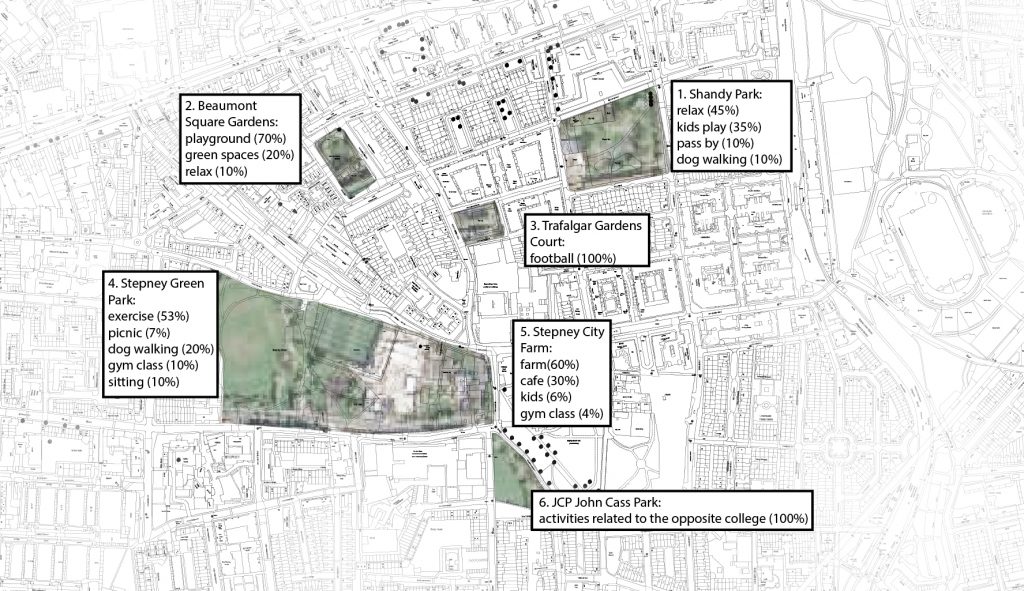

This topic was approached through a site analysis and interviews to the local people in the neighbourhood. The aim was to understand the variety of activities/options offered and different types of green spaces by mapping all the activities taking place in them, formal and informal ones. It seems that there were three types of green spaces based on this category:

- (1) the ones that offered more than one activities/uses – none of which defined the character of the green spaces (green spaces no.2,4);

- (2) the ones that offered more than one activities/uses – one of which, being the most popular one, defined the character of the green spaces (green spaces no.1,5) ; and

- (3) the ones that only offered one activity/use which completely defined the character of the green spaces (green spaces no.3,6).

The majority of the interviewees supported the type 2 green spaces, were not interested in visiting type 1 green spaces and deliberately opted not to visit the type 3 green spaces out of fear/inconvenience due to location. When asked to choose between having type 1/2 or 3 green space in the neighbourhood, the majority would choose the former.

An interesting point however, was on people’s preference towards type 2 green spaces over type 1. At a first glance, both types seem similar to each other offering a variety of activities/uses. The difference between them is realised when entering the two spaces. In type 1 green spaces, the available activities co-exist in the space without adding any special feature in the park which ultimately creates no interest whatsoever. In fact, the opponents of the all-inclusive green strategy, which seems to be the approach taken in this space, were trying to fight the exact point; the over-determination of the space imposes a co-existence of activities and people under the name of the community without, however, adding nothing more. Filling up the space with uses, just to tick some boxes for the planning requirements, is not merely enough to bring people together because this over-determined close system does the exact opposite, taking all the fun out.

On the other hand, type 2 green spaces have a special characteristic, something that makes them unique in the neighbourhood and this has something to do with the one of the activities offered there, the most popular ones. For example, Stephey City Farm is known in the area for the farm itself, whilst there are other activities available. The majority of the people might visit it because of the farm, but at the same time the rest of the activities have some value as well, partially due to the value of the farm. The different activities seem to co-exist peacefully creating a nice environment and attracting visitors from different social backgrounds on a daily basis.

The type 3 green spaces refer to the green spaces in the neighbourhood where only one activity is offered for example no.3 and 6. These green spaces received the most negative comments – people mentioned that they choose not to visit them because they either find no interest in them or they feel uncomfortable being there, because these green spaces are mostly frequented by specific groups of people. As a result, these groups have gradually and unofficially claimed the space excluding everyone else.

It seems that the feeling of exclusion is mainly witnessed in green spaces where the number of activities offered is limited and so is the range of people it attracts. Green spaces no.3 and 6 only attract people interested in football or those studying in the school next to it. On the other hand, no.5 attracts people interested in more than one thing, visiting animals, having a coffee, buying local products, visiting the playground with the kids etc. Thus, the variety of people attracted in green space no.5 is naturally wider.

Concluding, the activities offered in a green space can affect the feeling of inclusion in the neighbourhood. Green spaces must be interesting and each should have a unique character to attract people. They should not be defined by one use only, but more to meet the needs of the wider community and attract a wider audience. The purpose of a green space is to be open to any possible user, not only the ones interested in football for example. The green spaces that offer only one activity, create inflexibility in the system and vomit out whatever else does not belong.

PARK USERS

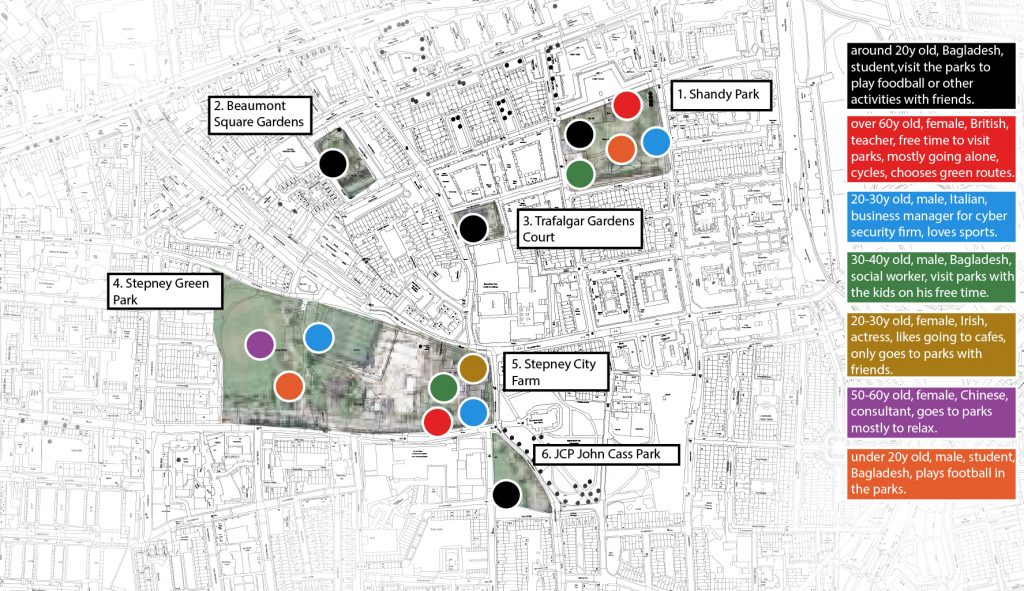

Overall, do people feel welcomed? Do people visit all the parks in the area or do they avoid visiting specific ones for a reason? Do they feel satisfied about the green spaces available in their area? Do people value proximity to green spaces? Based on the responses, the majority of the residents feel welcomed in all the parks of the neighbourhood, even though they mostly prefer visiting specific ones in the area.

An interesting fact here is that people’s preferences on green spaces do not depend on the proximity to them. Having mapped people’s housing locations and the green spaces they prefer visiting, it seems that proximity is not an issue when talking about neighbourhood scale. Harvey argued that fairness in the system can come only by equally distributing products in the city and the all-inclusive green strategy was based on this. However, when people asked to choose, they preferred to have a variety of types of green spaces in their neighbourhood, even if that meant having to walk a bit more to visit the one they want, than having green spaces with the same characteristics and close proximity to them. It seemed fairer to them to be given the opportunity of a variety of green spaces to choose from, than an equal distribution of similar green spaces around the neighbourhood.

The map below proves this point – distance is not an issue in neighbourhood scale. Therefore, a range of types of green spaces outweighs the equal distribution of all-inclusive types of green spaces. This is the exact essence of the park-system approach; fairness in the system linked to a variety of choices. This strategy also gives flexibility in a world that is constantly changing. The all-inclusive strategy cannot effectively work when the surroundings are changing. The park-system approach can adapt to the new dynamics of a place and change the balance in the system if needed. For example, in the all-inclusive approach, if one green space falls into decline, this will immediately affect the surrounding residents since they depend on this space because of proximity. In the park-system approach, if one green space falls into decline then people will go to another one, since this is the principle on which this approach is based; people visit any park depending on their daily preferences. In this way, the system can recover faster.

FINAL THOUGHTS & CONSIDERATIONS

Escaping to the countryside used to be a priviledge of the wealthy people. Only them could enjoy nature and cherish its benefits. This changed when nature entered the city but since then, there has been an ongoing fight for more green coverage and better quality to improve the welfare of the citizens.

Green spaces should not be treated as an accessory. The extent of the thinking process needed to design a green space should be equal to the one needed to design a building. As Abercrombie and others supported, the green infrastructure should be perceived as a system that connects the gardens with the green belt. Equal attention must be paid for both small and large scales.

Ocean Estate Neighbourhood is an example where both green strategies were applied and the outcomes can be witnessed. The park-system approach seemed to be the most appropriate ones for the reasons summarised below:

- Proximity. It was proved that people would visit any green space they like in the neighbourhood no matter the distance from their residence. Therefore, it is more important for them to have a variety of types of green spaces in their neighbourhood to choose from, than having many of the same type and only visiting the ones close by. The park-system approach supports variety of types and scales of green spaces that are linked together creating a nice green flow for people;

- Diversity and park uses. Green spaces should welcome anyone and avoid attracting only one group of people which results in excluding everyone else. The park-system approach suggests activities which give a unique character to each green space accompanied by other uses that can help build this character. Single use green spaces should be avoided because they attract a limited range of groups of people resulting in issues of exclusion and discrimination; and

- Diversity and park users. People feel more included in a green space where they witness a variety of people visiting it.

As I mentioned before, there were both positive and negative comments related to the green spaces and the feeling of social inclusion. The majority, however, was positive, supporting that for the last 5-6 years there has been an important upgrade of the area and the feeling of social inclusion in green spaces. Surely, there were some issues identified in the area regarding specific green spaces, but overall more than 90% of the interviewees felt positively about the green spaces in their area.

The park-system vision does not aspire to completely remove any feeling of social exclusion. This would be unrealistic. However, it aims to create a system of green spaces in a neighbourhood level that can provide a good variety of options for people; social inclusion can be achieved through this. What seems to be important to the locals is not visiting all green spaces available in their area, but to have at least some of them they feel comfortable visiting. This is more possible to be achieved in the park-system approach because of the variety it suggests, than in the all-inclusive one.

You can also download the full version of my dissertation below: