Does “sense of place” make any sense anymore?

I recently came across two very interesting readings that led me to today’s blog post; “More or Less Meaningful Concepts in Planning Theory” by Nigel Taylor (2003) and “On Bullshit” by Frankfurt H. (2005). Both books talk about the ambiguity that characterises many aspects of our culture which constantly fails to give real meaning to things. Frankfurt quotes that “one of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit”, whilst Taylor, following a similar approach, focuses on urban planning theory and stresses that the ambiguous and bad concepts are extremely hard to use in the urban design practice and are thus, less meaningful.

Take “sense of place” for example. Commonly used, but widely misunderstood, its definition ranges from concrete: “sense οf place is having an abundance of open spaces, so people feel closer to nature”, to more abstract: “sense of place is the feeling of belonging in a place”. For this term to have any meaningful impact on urban design practice, these abstract definitions need to be replaced with a toolkit that clearly defines all the parameters that make this term. Quite a challenging task.

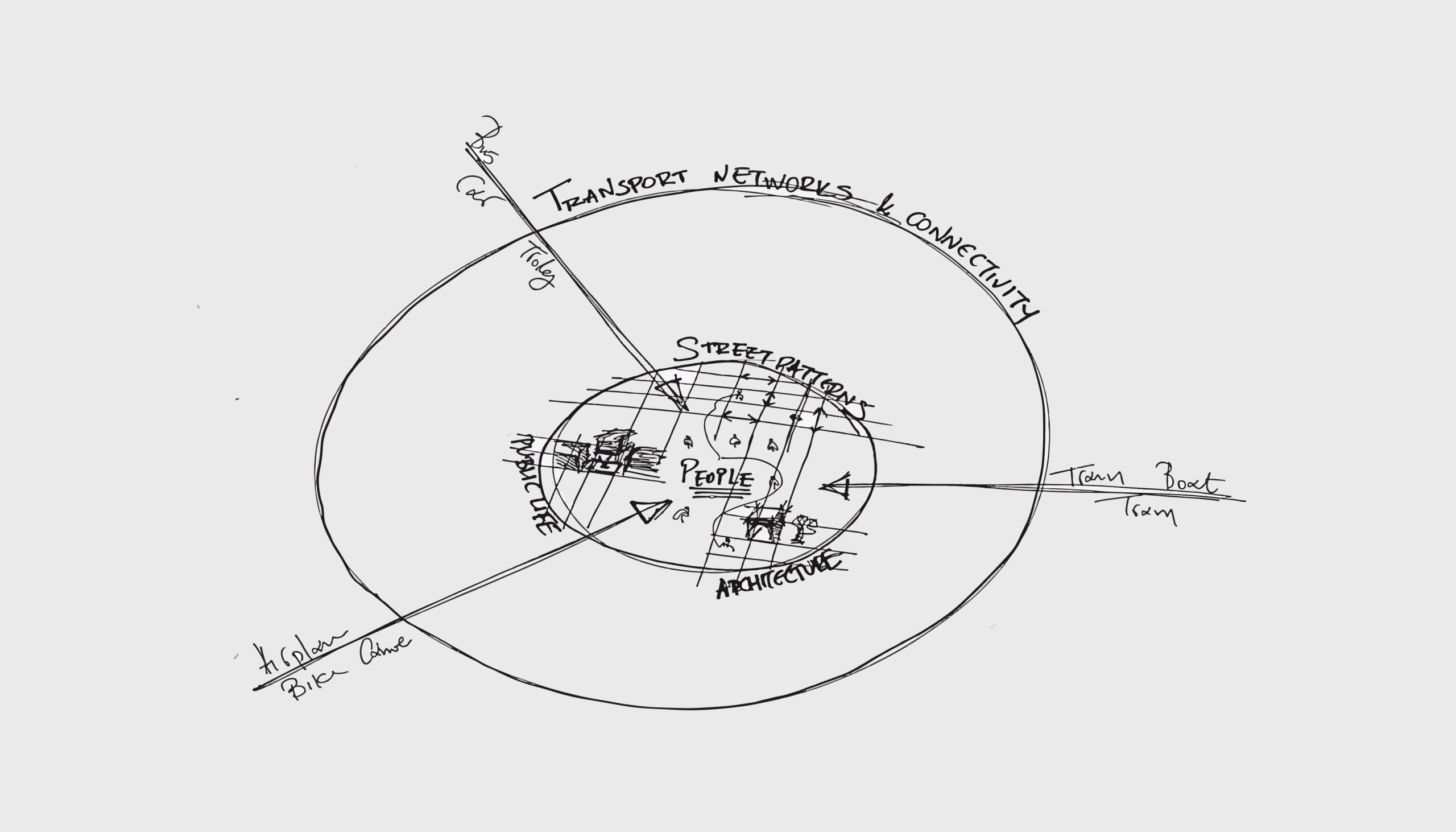

Some thoughts on some components that could be included in that toolkit are presented below. The ultimate goal would be to list out all these key elements that make a place and ultimately, shape the experience a person has in it.

- Transport infrastructure

- Street patterns

- Architectural styles & details

- Public life

- People

1. TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE

The way that wider and inner networks are laid out, or not, can tell much about a place. People move around and their experiences take form along the journey. Take two extreme examples; a metropolitan city and a remote island. By default, one would expect a highly efficient transport network in the first place aiming to serve great numbers of travelers on a daily basis and an off-the-map place in the latter one.

In cases where expectations meet reality, everything goes smoothly – people are happy and the “sense of place” is fully aligned. A negative experience on the other hand, can be caused by a misalignment between the “sense of place” and the existing infrastructure. Overall, this is the essence of place-branding; creating an identity of a place and then making sure that the expectations that this identity generates are aligned with how the place operates. The examples below offer a more detailed view on this:

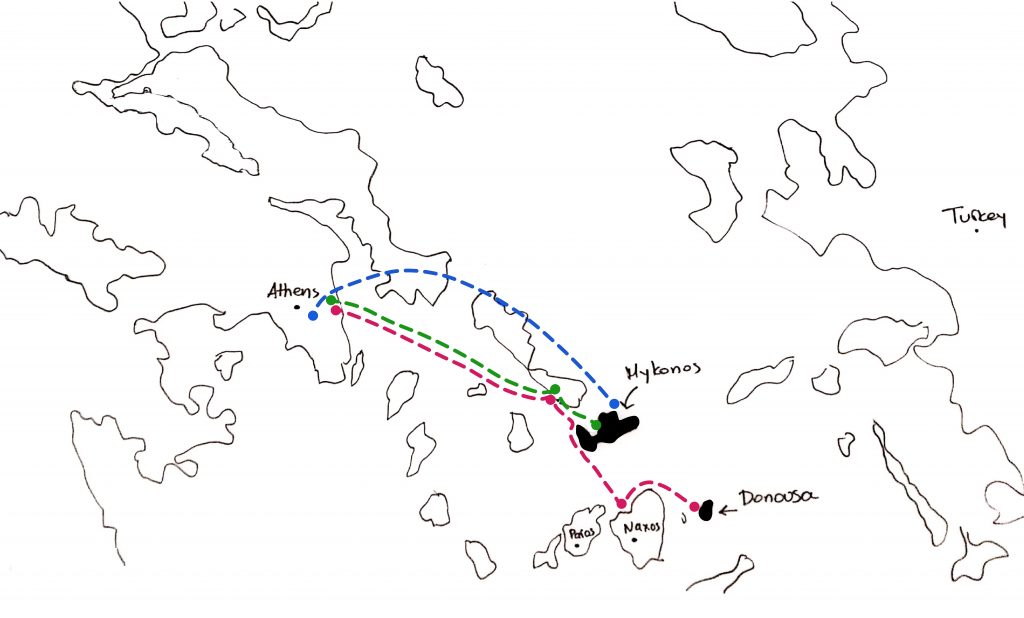

Example 1_Donousa vs Mykonos island: Donousa is a small island of an approximated area of 13 km2, quite remote, whilst Mykonos is much bigger with an approximated area of 105.2 km2 and a popular destination, nationally as well as internationally. Overall, each island is different in character and the approach taken with the transport infrastructure is in full accordance with the promoted “sense of each place” and people’s expectations. More specifically, limited boat services are running daily to/from Donousa, as opposed to more frequent ones running to/from Mykonos, including flights. Both places offer the amount of convenience they are supposed to offer. Overall, every option comes with a package and as long as it is successfully advertised, the “customers” are satisfied.

Example 2_London: Being a metropolitan city, London belongs to the “extreme” as it offers a complex transport infrastructure that serves millions of people on a daily basis. Many airport options, good connections to railway routes, plethora of tube lines and interconnections and bus services operating all day long etc. When moving around London, one can feel the dynamic of this metropolitan city.

2. STREET PATTERNS

Street patterns can also tell much about a place. Its age, hierarchy of moves, central avenues, little alleys. A historic core differs from a modern development and this can be easily seen only by looking at street patterns. Organic cores and meandering streets generate a different feel compared to permeable patterns and regular building lines. Street patterns are a point of reference for places and they should be preserved. Taking away those, you instantly take away an important part of the history. The examples below offer a more detailed view on this:

Example 3_Rome, Italy/Athens: Both cities are characterised by organic street patterns in their historic core, proximity to heritage assets and compactness. The narrow alleys offer high levels of enclosure, accommodate retail and commercial uses and act as a showcase for local architecture.

Example 4_Berlin: Berlin is an exception. The typical organic historic core cannot be found within the urban fabric, since the entire historic centre was destroyed and never rebuilt to its prior state, during the war. The only features that act as reminisces of the past, and mark the area which used to be the historic core, are the historic landmarks which are spread around. The lack of a historic core creates a slight confusion in navigation, especially for first time visitors, as it is a quite important reference point.

3. ARCHITECTURAL STYLES & DETAILS

The local vernacular plays an important role in preserving and enhancing the overall “sense of a place”. Design guidelines for new developments stress the importance of architectural styles and details for the preservation of the history of a place:

- New development should respect the existing local vernacular and make the most of the local materials available in the area.

- New development should embrace the modern techniques and sustainable design, whilst respecting the local vernacular.

- Housing extensions and conversions should be sensitive to the local vernacular of the surrounding context.

- The list goes on.

Those guidelines are there for a reason and the preservation of the local character of a place must be a continuous effort by all parties involved. The biggest challenge is when new development comes within an existing urban fabric. The building typologies, architectural styles, massing, rooflines of the new buildings need to be sensitive to the existing built environment to help preserve the character of the place.

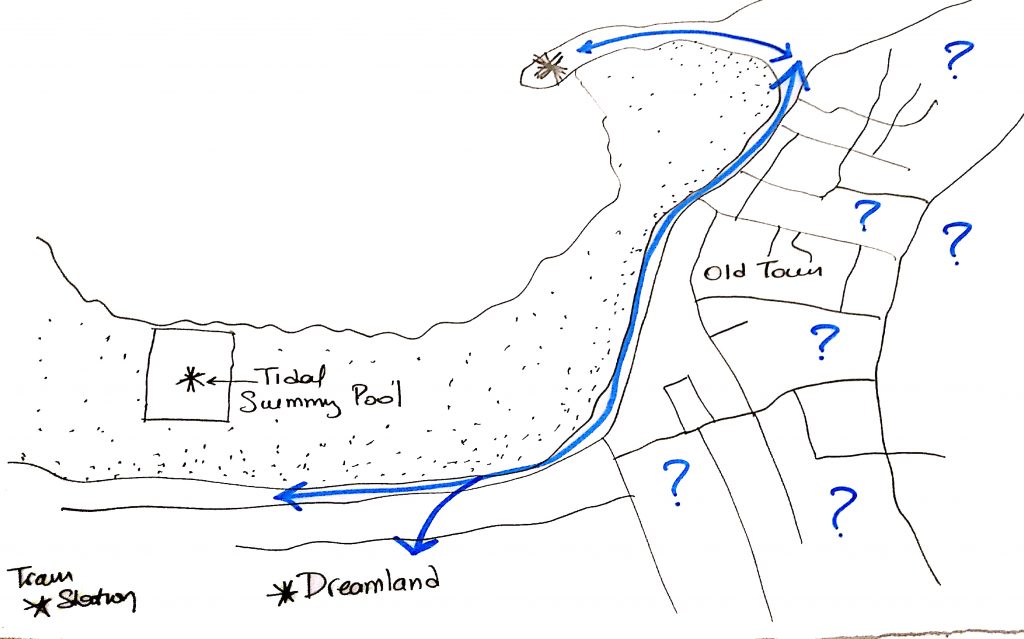

Example 5_Margate, UK experience: Speaking about sensitive developments, Margate is an interesting example to explore. Seaside towns in England used to thrive in the past when the fishing industry was booming. The town centres were usually found further up away from the seafront for extra protection during winter times. In recent years, the image of those cities, and Margate in particular, has changed and the focus is now on reactivating the waterfront. Public realm regenerations and tourist attractions have enhanced movement and brought life again along the seafront leaving, however, the town centre less active and vibrant. Those new attraction points have benefitted the town, but at the same time they tend to “distract” movement and “mislead” visitors resulting in a partial understanding of the place and thus, its real “sense”.

4. PUBLIC LIFE

The “sense of a place” can be experienced in both the intangible and tangible things. The everyday life in a place is an example of an intangible element which, should, carry the history of a place and give information about the past. History cannot only be found in museums, landmarks and books, but also in casual moments when walking along the street. Public open spaces concentrate activity and bring those moments into life. Parks, squares, streets can offer so much information about a place to the designer’s eye. Some questions, to ask oneself, to get some insight about a place are:

- Are there open spaces?

- If yes, are they private or public?

- Does the demand for open spaces exceed their amount?

- Do people visit those places as part of their everyday routine?

- What kind of activities take place in those places?

- What is the quality of the street furniture?

- Do people interact with each other?

- Do shops operate long hours?

- Is there a vibrant nightlife?

- Are there many shops operating during the night?

- Till what time does the metro operate?

5. PEOPLE

Last but not least, the people. By far, my most favorite category. People can give so much information about a place by talking to them or only by watching them. Funnily enough, the latter tends to give more accurate results as quite often we tend to express other people’s opinions than ours. But patterns do not lie. Mapping down movement patterns, most visited places (parks, squares etc.) or even underused areas can offer many insights. There is a reason behind these patterns and every time it is proved to be right. People flows can give information about issues or opportunities in connectivity, lack of pedestrian accesses, safety issues etc.

Example 6_Mexico City: An example from the book “Las reglas del desorden” by Duhau E. and Giglia A. (2008) can fit nicely here. The writer talks about disorder and order in design and argues that even though in many cases it looks like disorder prevails, in reality there is a layer of order as well, maintaining a balance. In metropolitan cities for instance, chaos and thus disorder is apparent, but if you look closer, then you see order in the way people manage to communicate, cooperate and eventually create their own rules to monitor places. A square in Mexico city is given as an example to illustrate the point; it is located in the centre of the city and it is filled with plastic bottles of water below the benches. Any “outsider” would comment about how dirty and badly managed that square is. However, what is really happening is a form of a closed system organised by the locals in an attempt to prevent dogs from peeing around the square; hence the bottles under the benches.

Overall, the above toolkit tries to give some clarity in the definition of “sense of place”. The different elements, once combined, offer pieces of information that can shed some light when analysing a place. Information that is place-specific and not generic, custom made and not a template.