Is it finally time for an upgrade to the centralised Greek planning system?

Greece is considered to be one of the most centralised countries in Europe. This fact, however, did not just happen over the night or under the commands of just one person. Studying the Greek planning system and its evolution can shed some light on the general context and the reasons behind this centralistic behaviour.

After a quick overview of the Greek planning history, this blog post will offer some ideas, taking examples from planning systems from elsewhere, to challenge the existing planning process and advise on ways to give citizens more responsibility and an active role in decision making.

OVERVIEW OF THE GREEK PLANNING HISTORY

The country was characterised as fragmented after the Ottoman Empire with local communities playing an important role in the political scene and having a high level of autonomism. After the War of Independence, in 1833, Capodistrias, the first Governor of independent Greece, tried to impose a centralised governance system making him an incomparably more authoritarian figure from his successor, Otto I, the Bavarian price imposed on Greece. This new administration abolished the local administration structure and established the new capital of the State in Athens. As a result, the local notables moved to Athens joining the central government as intermediaries between the centre and the rest of the country.

A grand territorial reform took place following this centralisitic model including obligatory amalgamations and imposition of a territorial consolidation similar to other European examples. In other words, territorial fragmentation was seen as a handicap to the creation of a unitary state and European integration; both seen as opportunities for economic development, efficient planning, and local democracy. In less than a century, the country had become increasingly centralised and Athens was now the centre in terms of economy, networks and population. Any planning decision for the whole territory was to be taken at the centre, Athens, with local authorities losing power.

In the meantime, public opinion seemed to disapprove of the territorial consolidation and the centralistic behaviour supporting that both resemble authoritarian attributes. After the fall of dictatorship in 1974 and the constitution of the 3rd Republic, the State administration headed towards decentralisation and it was pointed out that centralism should be overcome on the way to Europeanisation and modernisation of the State and politics. Decentralisation was a priority in the reform-agenda.

As a result of this, the Greek law established a second tier of local government, in 1994, at the level of prefectures aiming to strengthen the competence of municipalities and enhance people’s participation in the planning process. Regionalisation was also in the agenda, however, no action was ever taken apart from the organisation of the Greek territory into 13 regions. These were not part of a third level of self-administration, but the non-elected officials were directly appointed by the government and represented the State authority.

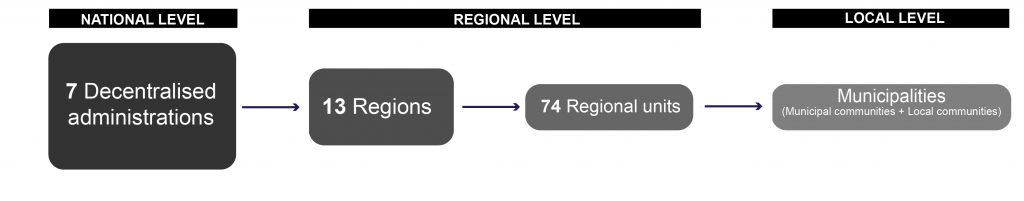

‘Kapodistrias plan’, in 1997, was the second major attempt towards this direction, proposing the restructure of the first tier and the creation of a new second tier that would support municipalities. This reform, despite its failures, changed the local government landscape and it was a start of a more modernised local government system. ‘Kallikratis plan’, in 2010, is the most recent reform, being implemented in 2019. Thus, the most up to date structure of the Greek administrative divisions can be seen in the diagram below:

CURRENT ISSUES FROM A POLITICAL & SOCIETAL ASPECT

Unfortunately. even after the reform, the responsibilities of the municipalities were limited to advisory and managerial tasks leaving no room to have a say in the policy making process. In particular, their responsibilities are limited to public functions for example construction and maintenance of public buildings, urban public transport, municipal roads, cemeteries, waste and water management, car parking management etc. Any policy making decision is taken by the State and its organisations (Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning and Public Work) questioning how decentralised the system actually is and how involve or not regions and local authorities are.

It is fair to say that the intentions to create the second tier self-government entities were not successful. The centralistic behavior still characterises the Greek planning system even at a local level since municipalities do not offer opportunities for public engagement whilst the mayor holds most of the power.

INSPIRED BY THE UK PLANNING SYSTEM

My personal working experience in the UK, led me to try extracting good practices and tools that could be proved useful in the Greek planning context or even offer some inspiration. The Neighbourhood Planning tool is a good example.

OVERVIEW OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING

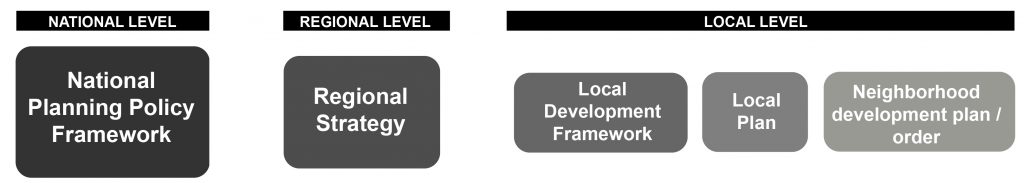

Neighbourhood planning act came into power in 2017 and it was intended to strengthen communities and give them the opportunity to actively participate in the planning decision-making process at an early stage. It is not a legal requirement but a right which communities in England can choose to use. The table below shows the existing UK planning tools and where Neighbourhood planning sits:

What is its use? Communities can have a direct power to develop a shared vision for their area and shape its development and growth. They are able to choose where they want new homes, shops and offices to be built, have their say on what those new buildings should look like and what infrastructure should be provided. Neighborhood plan provides a tool for local people to plan for the types of development to meet their community’s needs.

What effect can it have? Neighbourhood plans cannot act outside the scope, development plans or strategic policies set by the National Planning Policy Framework. However, they can be used as a material for consideration in many cases and affect the way in which development will occur. People in the community can set out a vision for how they want their area to develop over the next 10, 20 years with the help of local authorities that provide their support, advice and information when needed. The Neighbourhood Plan attains the same legal status as a local plan once it has been approved. At this point, it comes into force as part of the statutory development plan.

What is the role of local planning authority in neighborhood planning? The local planning authority should provide advice for any matter and take decisions at key stages in the process. It should set out a clear and transparent decision making timetable for the preparation of the Neighborhood Plan, engage with the community throughout the process including when considering the recommendations of the independent examiner of a Neighborhood Plan.

Summing up, there is an horizontal and vertical coordination of responsibilities in the UK planning system and a constant input from different levels. Indeed, the national strategies and goals are set out at the national level, but local planning authorities have the responsibility to put them into force the way they think is best, through the production of the local plans and development plans. Neighborhood Plans came later to reinforce this process and add people’s input as well. Local people’s opinion is used to better shape the high level national strategies and make sure the character of their area is preserved and developed the way they want. As stated before, the Neighbourhood Plan cannot go against the strategies and development plans set out in the higher levels, but it does have the right to advise on the implementation or make proposals on where the development should take place. This right not only does it give people the opportunity to have a say in the planning process, but also it keeps them well-informed and engaged with what is going on in their area.

GREEK SPATIAL PLANNING TOOLS

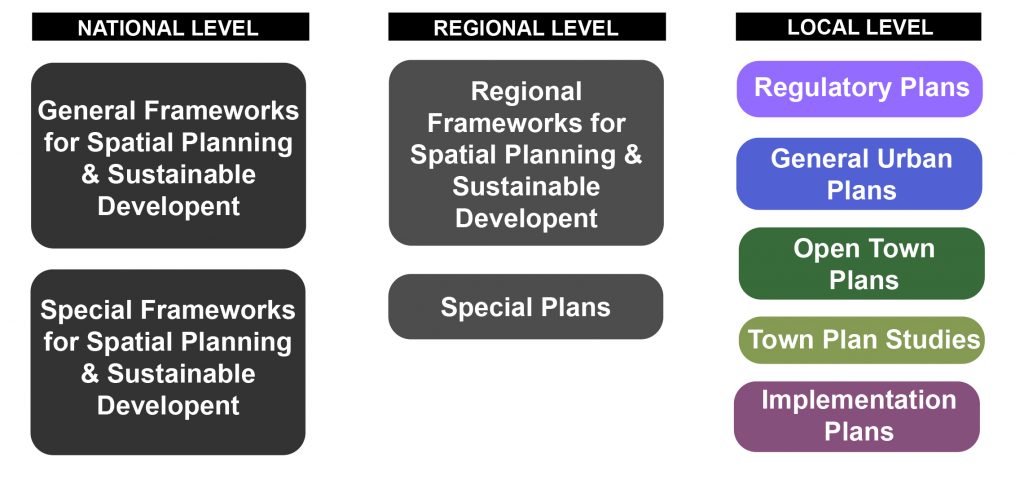

On a national level – General and special frameworks for spatial planning & sustainable development present high level goals and strategies for the development of the country in any aspect.

On a regional level – Regional frameworks for spatial planning & sustainable development present high level goals and strategies concerning the regions and their development.

On a local level – Regulatory plans and general urban plans or open town plans; the latter are produced through town plan studies and implementation plans. These are important tools of spatial planning at a local level and legislate the existence of a town or village and stop the unauthorised development.

People’s involvement in the production of any of the above is non-existent and their participation in the planning process is limited to public gatherings organised by the municipality during election periods. Civilians are not at all involved in the preparation of the above plans and their views are almost never really heard.

MY PROPOSAL – LOCAL PLANNING

What is missing from the diagram presented above is a tool with legal status that would enhance people’s participation in the planning process and give them the opportunity to share their views on how they want their area to be developed. A tool similar to Neighbourhood planning, let’s name it Local Planning for the purposes of this blog post, sitting below the General Urban & Open Town plans.

The Local Planning tool would be composed by municipalities in cooperation with the locals. The final outcome would be a report that would cover a particular municipality within a particular regional unit. This report could potentially include either or all of the packages below:

- A local character essay: a summary of the municipality presenting its strengths, weaknesses and opportunities in order to give an overview of its potential in local, regional and national level. The purpose of each area would be to present a good case of how its characteristics can be linked with the high level strategies set out by the State on a regional and national level;

- Site allocations: a list of identified opportunity areas that have not been designated for development by the State. In particular, local landowners will have the right to come forward and propose to sell their land to unlock development in areas that they believe there is opportunity for development with great potential benefit for the community;

- Design codes and masterplanning: design suggestions on areas of interest highlighted in General Urban and Open Town plans. These suggestions can include:

- Small – medium – large ideas on how to further improve designated open spaces;

- Business proposals, with business case study attached, related to designated areas for development; and

- Set of design codes related to buildings, open spaces, public realm expressing ideas on how they would want their area to look like in case any future development comes.

The Local Planning team would consist of local people and businesses that live in the municipality. There should be a diversity of professions, ages, ethnicities to reassure equal representation of all groups of people.

The locals will work closely with local authorities to have access to information needed to build the evidence case for the Local Planning report as well as to gain a deeper knowledge of the planning process, policies and systems. In addition, the State in cooperation with the Ministry of Environment, Physical Planning and Public Work (YPEXWDE) should allocate representatives to each group that is interested in using the Local Planning tool in order to educate them over the national and regional strategies that have been set out. By doing so, the local people will be better educated and feel more confident when proposing ideas.

In terms of process and submission, the Local Planning report, after completion, will be submitted to the local authorities for approval by the Regional Governors of each region and the General secretary of each decentralised administration. They will need to make sure that it is aligned with the National and Regional Frameworks. This tool would not surpass the development decisions and strategies already set out on a high level; it would be an advisory tool only aiming to shape development in a way that would satisfy the local community.

IMMEDIATE BENEFITS

Getting to know each area better: Local people know their area more than anyone. They are fully aware of the issues, the opportunities and the hidden beauties. Thus, working with local people to prepare the local character essay will ensure that all matters are successfully covered. In addition, a healthy competition between municipalities will start improving the quality of outcome.

Unlocking development through locals’ initiative: Giving the local people the chance to identify opportunity areas or come forward proposing developable land might facilitate the process. Keeping local people closer to the decision-making helps create a new, positive, attitude towards development.

Educating people into design: The ultimate goal for any new development, in an ideal world, is to satisfy the locals and improve the quality of life. Giving people the opportunity, through the Local Planning, to suggest ideas on how they would shape any future development in their area educates them into design. With this tool people become masterplanners themselves.

LONG-TERM BENEFITS

Horizontal cooperation will be enhanced. Local Planning tool is a bottom-up approach that will give local people the opportunity to play a role in the planning process and also educate themselves into the planning process. The majority of the local people have no knowledge of the planning process and therefore, their contribution into the consultation gatherings is limited.

High level national and regional frameworks will finally have an impact on the local level. Unfortunately, the high level national and regional frameworks are not well linked with the General Urban and Open Towns plans. The Local Planning tool will help bridge this gap suggesting policies and proposals that are aligned to national and regional policies. Any proposal on the local level should be in full accordance with the high level strategies set out by the State.

Urban design as a field of study will be promoted. In a country where architecture and civil engineering are the main fields, this new tool could give a push into the right direction. Working on a high level framework, establishing policies and strategies in the context of a long term plan, could increase the awareness of other paths towards urban planning, town planning and urban design.

Overall, the Local Planning tool could help both parties: 1) local people will be given the opportunity to present their views and ideas and 2) the State administration will start cooperating with people, truly address their needs and also discover better ways to promote each region.

FINAL THOUGHTS & CONSIDERATIONS

Greece is characterised by a strong territorial fragmentation. It is composed of rural, coastal and mountainous areas along with peninsulas and islands. The formation of the country’s territory is unique in Europe and this characteristic presents its strength, but also challenge.

Regionalism could potentially thrive in Greece and become a great marketing tool for the country benefiting tourism and therefore, the economy. The recent regional strategies created by the State have not managed to strengthen the regions whilst the input of locals is missing. A new approach should focus on horizontal cooperation where locals and local authorities will work together contributing to the State’s work in promoting the regions. In an ideal scenario, the State should be responsible for setting out a clear vision and objectives, nationally and regionally, whilst local authorities and local people should take these into account and try to bring forward actions and proposals on a local level.

I believe we are going in the right direction with the creation of the national and regional frameworks showing a positive intention. Moving forward, we could start adopting tools used in other planning systems around the world tailoring them to fit the Greek context.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Asprogerakas, E. (2016), Strategic planning and urban development in Athens. The current attempt for reformation and future challenges

- Asprogerakas E. , Wassenhoven L., Karka, L., (2002), Planning towards European enlargement: the Greek and Bulgarian planning systems

- Kapsi C., M. (2000), Recent administrative reforms in Greece: Attempts towards decentralisation, Democratic consolidation and efficiency

- Klimovsly D., Swianiewicz P., Wollmann H., (2010), Territorial consolidation reforms in Europe

- Komninos-Hlepas N., (2017), Regionalism in Greece

- Komninos-Hlepas N., Archmann S., Grigoriou P., Kastelan Mral M., (2011), Public administration in the Balkans from Weberialn Bureaucracy to new public management

- Komninos-Hlepas N., Kersting N., Kuhlmann S., Swianiewicz P., Teles F., (2018) Sub-municipal governance in Europe, decentralisation beyond the Municipal Tier