Designing for an urban extension, somewhere in Suffolk

GENERAL INFORMATION

- Location: Suffolk, UK

- Area of study: Land adjacent the existing settlement

- Professional work | AECOM | 2021

GENERAL CONTEXT

This project is part of a Neighbourhood Planning package funded by the government where AECOM was commissioned to provide technical support to a market town in Suffolk in relation to an upcoming mixed-use development in a land adjacent to the existing settlement. A masterplan for the area had already been drafted and proposed by a developer, however, the locals felt that it did not entirely reflect the key characteristics of the area and their views. For that reason, they wanted to produce their own masterplan to use as a tool for potential discussions with developers and other parties. This is where our design team came in, to initiate a series of workshops with the locals in order to understand their views and concerns and to ultimately propose an alternative masterplan; one that would entirely represent their views and ‘good practice’ urban design principles.

DESIGN PROCESS

So, starting the design process, a series of design workshops were organised to engage with local people and listen to their views and concerns. The first round was focused on the issues and potential opportunities of the study area, whilst the second was oriented around the new masterplan. In both, local people’s contribution was a key driver for any design decision. Some summarised notes taken during the workshops are presented below:

Issues & opportunities:

- Challenge on successfully linking the new development with the existing settlement through pedestrian and cycle links. One of the main concerns for the locals was the creation of a fragmented new community where people feel isolated from each other;

- Environmental constraints related to woodland, flooding, heritage and noise distraction needed to be considered in new development and integrated into the design proposals;

- New development, if designed properly, would benefit the existing community too. A range of new facilities (retail, shops, education) would come to the area to not only be used by the newcomers, but also by the existing community; and

- Opportunities for more connections to the surrounding countryside and open fields. New development could help improve existing links or propose new ones.

A set of ‘good’ design practices of other town extensions of similar scale were presented to the locals to give them some indicative illustrations of the design principles that could be applied in the study area. Those extensions were sympathetic to the surrounding environment, sensitive to the existing architectural context, while welcoming contemporary design too.

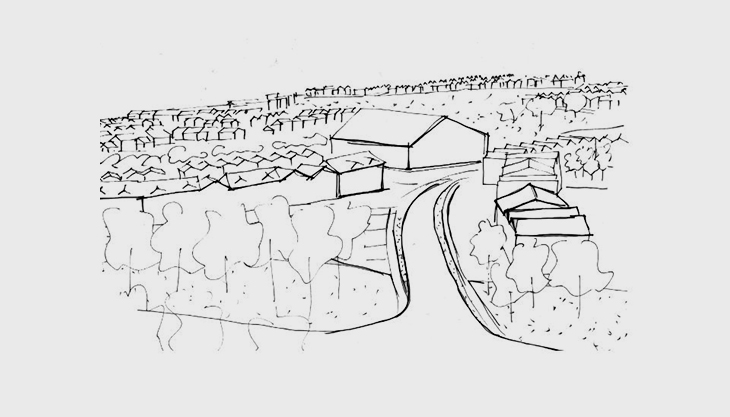

After discussing the above exemplars in relation to the street network, street typologies, open spaces, build form and architecture style and details, then, during the second workshop the design team presented the new masterplan explaining how all those principles were applied. The notes and 3D illustration of the proposed masterplan presented below summarise the basic principles:

- Connection with existing settlement. Pedestrian and cycle routes were proposed to secure direct links to the existing community, facilitate movement and enable people to enjoy the existing and new facilities;

- Connection with the surrounding countryside. Pedestrian and cycle routes were proposed to secure direct links to the open fields to the west and east side of the study area. These links were strategically located within the site, in close proximity (no more than 400m walking distance) from residencies;

- Permeable street network and perimeter blocks. Permeability is important to improve pedestrian, cycle and vehicular movement. Cul-de-sacs, which thrive in some locations in the UK and are often a characteristic of new developments, were kept to a minimum in this masterplan and they were always connected to a footpath;

- A good range of local facilities. The provision for local facilities included a small scale local centre, employment area and a primary school. The location of these facilities was strategically proposed by the entrance of the new development and opposite to the employment area to attract movement from the main road, while also being in close walking distance from the new and existing communities;

- Buildings always facing the street. It is part of ‘good’ design practice to always have buildings facing the streets. This not only improves natural surveillance, but also creates active streets where people feel safe walking along and interacting with their neighbours. Long blank walls, on the other hand, can cause the exact opposite; unpleasant street scenes where activity is discouraged, and people feel less safe;

- Green park system. A variety of open spaces was proposed; informal parks, playgrounds (6a), woodland (6b), linear formal parks (6c), a public square (6d), sport field (6e) and allotments (6f). Those green spaces would have different character and offer a wide range of uses. Through my personal research, part of my dissertation, I found that having different types and scales of parks within a neighbourhood offers many positives to the local people compared to only having one type of parks. A variety of types of parks would succeed in meeting the needs of a wider group of people, while also securing social inclusion and providing a level of resilience to any socio-political, and other, changes; and

- Wayfinding and signage system. A legible place helps people better orient themselves. The use of signage (in the form of totems, interactive totems, sign posts, QR codes etc.) in strategic points within an area can effectively navigate people around and inform them about important destinations. In addition, the configuration of the streets and buildings can also improve legibility in an area. In particular, landmark buildings, large street trees in the corners, art installations in the open spaces and key short or long-distance views can create memorable places.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

The unprecedented rise of housing needs in the UK has led to a continuous hunting of vacant land to build in. Urban extensions is one way to deal with this need as it definitely has its advantages; there is already an existing infrastructure, services, population and community which is usually more attractive to prospective buyers. However, urban extensions come with their challenges as well. Design schemes need to make sure they create a community that is well-connected to the existing settlement and avoid fragmentation. To achieve this, a variety of design principles should be applied in terms of street network, pedestrian and cycle connectivity, location of the new facilities, architectural style and details, building lines, typologies etc. Overall, it is important that all the above are designed by taking the key characteristics of the existing settlement as a reference. The final outcome should feel the same, only better, and together, the existing and the new, should create a unified visual result.

There have been good and bad design practices concerning examples of urban extensions. Good practices focus on creating pedestrian connectivity between existing and new communities, preserving the local vernacular, strategically locating any new facilities within close distance from communities and so on. In other words, good practice, and this is what differentiates it from the bad one, considers the local context and respects the needs of the existing population. One of the most important parts of the design process is the feedback that comes from the local residents. Their contribution and comments are very important, and they should be taken into account during the design process. It is not always true that local communities are opposed to any new development, but it is true that they want what is the best for their area. They do not want to be isolated from the new community and they definitely do not want some modern developments rising with no reference to the architectural character of the existing settlement. This is fair! So, during the design workshops with the locals, the overall aim for us, the designers, is to understand their needs, address them in the design and then, explain to them how this fits nicely into the local context.

One last point would be about the 3D illustrations and how useful they are during this process. People with no design background tend to find it easier when put in front of a 3D sketch or even an indicative image as opposed to an illustrative map. When all the design proposals are laid out in a 3D sketch or diagram, they are easier to comprehend and imagine in the space. In addition, those graphic tools are useful for designers too, since it is an easy and quick way to discuss and evaluate a design idea, in all dimensions, with other colleagues.

Note about graphics: This masterplan was first created in Revit and then imported in Rhino to add all the materials, since it is far easier to edit materials in Rhino than Revit. The final touches, vegetation and labels, were done in Photoshop.